Module 2 - A Reflective Essay Justifying Social-Constructionist Epistemologies and Methodologies In Music Education Research

- ricketts15

- Feb 19, 2024

- 19 min read

The relevance of social constructionism in educational research.

"The distinguishing feature of research is that it is published so that it can be reviewed by peers. Only then is a claim to truth accepted or rejected. The claim to knowledge is based on surviving criticism, not by reference to mysteries beyond human reason" (Shipman,1997, p4)

Educational research acknowledges an array of philosophies, epistemological, and methodological orientations. As a research practitioner, my methodological position is grounded in social-constructionist epistemology. This idea views knowledge as a co-constructed product of interaction and dialogue among individuals within specific social and cultural contexts (Bryman, 2008). Thomas (2017) recognises that acknowledging positionality is likely to affect the researcher's perceptions and identifies the "centrality of subjectivity" within qualitative studies (Thomas, 2017, p.112). It is also clear that acknowledging specific influences within positionality and understanding their impact on research is vital (Dunne et al., 2005). The music curriculum and its relevance, value, and history are primary research interests. This stems from my experiences as a student, a teacher, a curriculum leader and now a researcher. This gives rise to the idea that exploring the epistemology of knowledge alongside ontological reasoning is necessary within musical education research and the social sciences. In this essay, I aim to defend and justify using a social-constructionist ontology and interpretivist epistemology.

Furthermore, critical observations will be given on positionality. The limitations and criticisms associated with the social-constructionist worldview will be explored. Research interests will also be established. Firstly, an understanding and rationale behind this epistemology must be confirmed.

The core idea of the social constructionist epistemology is that language and social interactions generate reality rather than reality being an objective, preexisting entity. This point of view is in line and closely linked with the works of philosophers such as Vygotsky (1978), who emphasised how social contexts and language affect how each individual views the world. The idea of a socially constructed reality argues that historical contexts, common discourses, and cultural standards influence our perceptions, beliefs, and knowledge and that these must be considered when conducting the meaning of research data.

As a result of linking the multi-faceted idioms of social interaction, knowledge is primarily constructed through language. Social constructionism emphasises how language is a significant force that changes and influences our beliefs, perceptions, and relationships, drawing from the writings of Foucault (1972) and Shotter (1993). These philosophical underpinnings give a researcher-practitioner the groundwork to investigate educational phenomena through a lens recognising the dynamic interaction between personal experiences and the more extensive socio-cultural milieu. Gergen (1999) expanded on this with "mutual shaping", where individuals and the social world are intertwined, embracing the diverse voices and perspectives that shape our understanding of educational phenomena. Van Dijk (1993), Wodak and Meyer (2009), and Willig (2014) offer linguistic methodologies that focus on the direct and indirect power relations within the language of texts with Foucault and Derrida recognised as seminal theorists; this will be explored further in later sections.

Bryman (2008, p15) also links this interpretivist approach to phenomenology, an idea that the researcher is influenced by their experiences and how they make sense of the world around them, solidifying the link between knowledge and the social. This, again, is a direct link to the importance of reflexivity in research, the process of looking inward to your own experiences to make observations on your perceptions and, ultimately, challenge and identify them (Dunne et al., 2005). Furthermore, Elveton (2020) concludes that Husserl (1999) pioneered phenomenology and explains that it intends to understand perceptions, encouraging the researchers to immerse themselves in the experiences of individuals through careful methodological planning (Elveton, 2020). This supports identifying themes within data to influence the social understanding and perceptions of its nature. These reflexive approaches also apply to the researcher's interaction with the data and awareness of where potential biases may occur; it is vital to highlight these reflexive utterances to help unpick the data and why opinions may form on particular themes within the data (Thomas, 2017; Dunne et al., 2005). A further supporting criticism of phenomenology includes the lack of ability to handle a large amount of data effectively, concluding that the data interpretation could be subjective, complex and biased (Fink, 2003, cited by Elveton, 2020).

Social constructionism is particularly pertinent to examining the themes of identity, values, and power relationships in educational contexts. Critical pedagogues like Freire (1970) and Giroux (2020) have used social constructionist concepts to question established educational paradigms and promote transformational pedagogies that enable students to connect critically with their environment. Within Freire's (1970) "critical pedagogy", the social-constructionist values and principles are evident with social justice and the necessity to challenge dominant power structures at the centre of this epistemology. The researcher-practitioner or insider researcher understands the fluidity of educational situations and the possibility for change via discussion and cooperation by adopting the social constructionist viewpoint.

There are several justifications for using the social constructionist approach in future educational research. First, it moves away from the education system's top-down dissemination of information and acknowledges participants' agency. This idea is further supported by Dewey's (1938) concept of experiential learning, in which people actively generate knowledge through involvement.

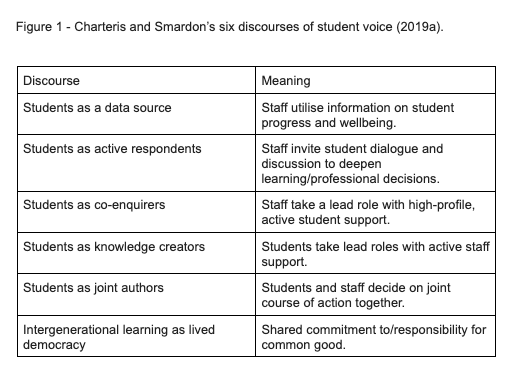

Secondly, the co-construction of knowledge inherent in social constructionism is particularly relevant in education, where diverse perspectives meet. Educational settings are microcosms of society, influenced by power dynamics, cultural norms, and personal experiences. Engaging with these requires an approach that values diverse viewpoints, much like Freire's (1970) "critical pedagogy" work. Examples of power struggles within the music curriculum can be seen in recent literature and research on student voice (Spruce, 2015; Clauhs & Cremata, 2020; Stavrou & Papageorgi, 2021), and the idea of a co-constructed curriculum with students would fall in line with the social-constructionist view due to its potential of a collaborative nature and the 'students as joint authors' model highlighted by Charteris and Smardon (2019). Stavrou and Papageorgi's 2021 study highlights some factors of students' voice and the challenges of prescribed topics. However, it remains synonymous that research around a co-constructed is limited and needs developing and will be mainly specific to the particular context where the research is constructed; this is clear when Stavrou and Papageorgi quote Griffin (2011, p89) saying, 'Children's perspectives need to be heard and their voices acknowledged as a central catalyst in shaping the planning, enacting and experiencing of music curricula'. The work of Charteris and Smardon (2019), who identify six discourses of student voice (Figure 1) that show that an approach to a collaborative curriculum should be taken with caution, is notable. This is due to the use of student's voice as a tool to direct and enforce a higher agenda within an establishment and use the idea of student agency as a tool for "organisational surveillance and discursive power" (Charteris and Smardon, 2019, p97).

A particular research interest is the development and structure of the music curriculum, which involves the content and knowledge studied or suggested within key stage three in English secondary schools (Ashbee, 2021; Steward, 2020). When conducting research in this field, it is vital to understand the perceptions of stakeholders and the influence of the many external factors to truly understand where and why value is given to specific musical knowledge. Some factors include the social perceptions of Music through time and how they have influenced music education, perceived national heritage and its impact on what is prescribed in national curriculums, and the influence of government documents on what is studied in core music lessons nationally. By understanding these social, historical and ethical factors of music curriculum development, relevant breakthroughs in context-specific musical curriculum can be co-constructed effectively, evaluated and implemented.

Interpretivist vs Positivist ideologies.

The discipline of philosophy known as epistemology, which examines the nature, extent, and boundaries of human knowledge, has historically given rise to several schools of thought. In this section, we will critically discuss positivism to justify the social constructionist epistemology within education research.

Positivism values the importance of using scientific techniques, empirical observation, and rigorous, objective methods to learn new things (Comte, 1975). Positivism immediately rejects the complex subjectivity of an interpretivist approach to research seen in more holistic epistemologies. Positivism emerged in the Enlightenment era and was used to challenge traditional religious and metaphysical explanations of the world built upon the empirical principles of physics and chemistry, later pioneered by Comte and Mill (Feichtinger et al., 2018). Hollis (1994) dives deeper into the distinction of positivism, showing its multi-faceted developments through time, but still acknowledges that positivist researchers are more often heavily reliant upon quantitative rather than qualitative data (Hollis, 1994, p42).

Understandably, due to the rigorous nature of positivist methods and their objectivity, there are many fields of research where this approach has been successful. Bryman (2008) concludes that there are many benefits to research through a positivist lens, including the lack of bias due to its reproducibility, systematic approaches that add rigour to the study, and structured methodology that analyses empirical data. Despite these positives within specific fields of research, educational research is rooted in the ideas and opinions of people. As a result, adopting a purely quantitative and objective approach may result in missing the complex human social phenomena that may arise (Babbie, 2016).

Why a social constructionist approach is relevant to studying the musical curriculum.

Within music curriculum research, there is a notable gap in research when looking at the release of recent government documents, including the National Plan For Music Education (NPfME) (2022) and the Model Music Curriculum (MMC) (2021). The closest study that bears relevance to this field is the work of Bate (2020), who uses Discourse Analysis to deconstruct the Music National Curriculum (NC); in this work, Bate (2020) concludes that the use of a musical canon as seen in the NC forces students to accept the social construct of musical value and accept the suggested "great composers" pre-defined by the social norms (Bate, 2020, p8). Bate also argues that an NC puts power in the historical musical discourse and removes autonomy from specialists in the classroom and relevance to those consuming this prescribed information.

As highlighted previously, there are many influences on what is valued in the current music curriculum. Priestley (2021) highlights the many factors that influence curriculum decisions. There is the micro (teacher), meso (school) and macro-political (government) standpoint, which all have an impact on curriculum design. Hargreaves et al. (2007) and Dalladay (2017) give an awareness of the effect of the micro and meso when they include teacher experiences, beliefs and background on the influence of curriculum decisions. Young et al. (2014) further this notion and highlight the tension often seen between teachers, schools, and government. Again, these theories and ideas exclude the student voice as a democratic model to construct a relevant curriculum.

Researchers must navigate the tension between subjectivity and objectivity to produce credible findings. Moving forward, this field is exciting and, with the correct methodological approach, could highlight dominant discourses that have shaped the musical knowledge valued in the curriculum. I intend to start my journey as a researcher-practitioner by conducting a Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) study on specific sections of these government documents. The final section of this essay will justify this choice of methodological research.

With a social constructionist epistemological viewpoint, it is essential to tackle problems reflexively (Dunne et al., 2005), understand significant factors that will influence the research, and highlight my knowledge of myself and how it may impact the research. The following section identifies and explores some factors that could directly affect the research I choose to undergo.

Positionality

I have a unique background in music education, having worked as a white working-class singer on cruise ships for under six years and been a touring solo musician for 15 years. My musical duties on the ship included entertaining vacationing guests with well-known songs. This is important because I was expected to understand less about music theory as a professional musician than I had learned for my GCSEs and A levels. This will affect how I feel about the music curriculum and the material taught. That opinion is that the current music curriculum needs to cater to the requirements of a professional musician in several settings. Daubney and Mackrills' four-year research project between 2016 and 2019 suggests the theory that music curriculum is irrelevant to the modern-day musician is true as they highlight the falling Key Stage 4 and Stage 5 (KS) numbers in music education and the diminishing provision nationwide.

Our incoming KS4 cohort, which starts in year 9, will take vocational music and music technology courses I recently launched. The vocational classes provide students with the tools to use technology, performance, genre analysis, and composition to explore their interests and motivations in music. This is due to the ongoing discussion around the relevance of Music with students in previous research. According to my professional judgement, the students in my context may have difficulties accessing the GCSE courses because of their musical preferences, cultural origins, and language proficiency levels.

Previous research has included semi-structured interviews with teachers and observations of students' responses to the curriculum while looking at behaviour, engagement, and reactions to musical choices in lessons (Ricketts, 2022). While conducting this research, I considered myself a novice researcher and explored these techniques at a rudimentary level as part of my MA course. Although elementary, the methodological plane described by Dunne, Prior, and Yates (2005) made me aware that the "contextual flux at all stages of the research process means that it is subject to pulling from different directions". This is the idea that many different factors are at play when looking into interpretivist research. These include power structures of the stakeholders involved, micro and macro political issues, ethical issues and practical issues. I was also made aware of the criticisms of Fink (2003). I experienced a vast amount of data that needed to be methodologically analysed and interpreted whilst being aware of potential bias due to my experiences.

Although a novice researcher at this stage, the research highlighted some critical conceptions of music education. A common theme that has resulted in this further research was injustice or the 'narrowing' of the arts due to establishments and higher power (Ricketts, 2022). This original research focused on understanding the extent to which students have input into curriculum design within the arts. Ultimately and broadly, this initial project highlighted the research gaps when looking at a student-led designed curriculum, galvanising this unobtrusive portfolio. Furthermore, the literature review attached to this research highlighted some strong opinions about music education. Spruce (2016) and Bates (2017) argue that the idea of a music curriculum that is "enforced" immediately allows dominant populations to shape content based on their musical and cultural values.

Moreover, Mark (2021, p105) highlights the importance of the relevance of a curriculum and suggests that without this consideration, "people lose interest, and it dies". With the falling number of people choosing Music highlighted earlier, it could be said that this is currently the case, and Mark's 2021 study falls in line with the student voice work of Spruce (2015) and Stavrou and Papageorgi (2021) that was previously explored. Mark (2021,1995) also highlights that music education is still rooted in past values of Music and society and is yet to be adapted and changed with current societal needs and values; this is something that falls in line with my research interests and is something I would like to unpick in more detail. Literature supports the idea that the role of Music in contemporary society has changed and is now harder to define, but currently, it does not offer many concrete answers. This further supports the need and value of this research. The following section will highlight reflexive biases that may occur as an insider researcher on this assignment and future assignments.

Insider Research

The research for the thesis of the EdD course will take place within my context, which immediately places me as an insider researcher. Insider research positions participants as co-researchers, acknowledging their expertise and lived experiences (Dunne et al., 2005). Here, the "critical pedagogy" work of Freire (1970) galvanises positionality, showing the transformational power of education when it is based on dialogic exchanges and lived social experiences. This section will highlight some positives and negatives of being an insider researcher.

Edwards (2002) highlights that insider research refers to a study conducted by a researcher who is a member of the organisation or social group being investigated. Edwards (2002) also notes that sustained participation in an organisation serves as a kind of validity. According to Merton (1972, p15), insider study enables an in-depth understanding of a specific social group because outsiders find it difficult to "comprehend alien groups, statuses, cultures, and societies." Furthermore, Powney and Watts (2019) praise the advantages of insider research as a unique look at "contextually rich data" that may be overlooked in a more quantitative study (Powney and Watts, 2019, p245).

However, with this comes the risk of personal biases that may affect the objectivity of the interpretation of data. Biases that I am aware of that could challenge the validity of research include my musical background, societal status, the experience of music curriculum as both a student and teacher and my musical preferences and experiences. My preferred style of Music to perform is that of the folk genre, and my instruments of choice are vocals, guitar and mandocello. My experience as a student in a heavily Western classical curriculum and teacher training shifting to informal pedagogies with varying success could shape how I view Music's relevance to students. It is also important to note that the context where I teach has highly diverse levels of deprivation, including some of the most deprived postcodes in the UK, according to the Index of Multiple Deprivation (Ministry of Housing, 2019).

Burr's (2015) observations are especially pertinent to insider research because they draw attention to the ethical dilemmas of adopting a social constructionist viewpoint. Reflexivity, or critically scrutinising one's prejudices and presumptions, is a crucial element of insider research, ensuring that the researcher's perspective does not dominate the results. Using robust methodologies might help to make this reflexivity explicit. In the next section, I will critically explore the method of CDA and justify its use in this unobtrusive assignment.

Critical Discourse Analysis as a chosen method.

Analysing data from a social constructionist perspective involves identifying discourse patterns, power dynamics, and shared meanings within the educational context, including language or text (Bryman, 2008, p. 19). This portfolio section explores some methods commonly associated with social constructionism and examines the strengths and limitations of CDA alongside Foucauldian analysis.

Discourse analysis, rooted in the works of Foucault but more recently evolved by Fairclough (2003) and Gee (2014), offers a methodological framework to uncover how language constructs and reflects societal norms and values. By examining participants' language, the researcher-practitioner can illuminate how educational knowledge is negotiated and reproduced. CDA focuses on three interrelated dimensions of discourse: text, discourse practice and socio-cultural context (Van Dijk, 1993; Fairclough, 1995). Van Dijk (2006) explains the importance of CDA and how language has been used to legitimise certain ideologies by highlighting that "manipulation of public opinion is one of the most important functions of discourse in society". Contributing to the field of CDA with a focus on the understanding of ideology and hegemony is the work of Laclau and Mouffe (1985), who claim language has a "discursive construction" to construct and reproduce specific ideologies linked to the social (Laclau and Mouffe, 1985, p105). They explain that discourse and social norms are constructed through political means. In music education, this would mean exploring and identifying the intention behind government documents and their value to specific musical knowledge in the curriculum. This idea reiterates the work of Fairclough (1995), Van Dijk (2006) and Wodak (2001), who are openly critical of the limitations and issues surrounding CDA.

Despite CDA being significant in research, there are several criticisms and limitations that its critical theorists highlight. Fairclough (1995) and Van Dijk (1993) recognise the risk of overemphasising power relationships leading to essentialism, which states an oversimplification of complex social dynamics and an inadvertent reinforcement of existing stereotypes and misconceptions. Furthermore, Wodak (2001) and Fowler (1997) argue that it is impossible to remain objective whilst engaging in the interpretive method of CDA. These limitations link with the researcher's need to understand their positionality and the broader socio-cultural context surrounding the research, as Dunne, Pryor and Yates (2005) highlighted, further supporting the social constructionist lens for educational research and its intertwining of inductive and deductive methods.

Closely intertwined with the idea of CDA is the use of Foucauldian analysis, which has undeniably shaped and contributed to the field of philosophy and cultural studies research. Significant studies using this methodology can be seen in the seminal works of Butler (1990) and Hall (1997), referring to identity being shaped by the representation of dominant discourses that reinforce stereotypes and suggest cultural norms. The influence of these works indicates that Foucauldian analysis and CDA are robust frameworks for understanding the interaction between power, knowledge, and society.

Final Critical Thoughts & Validating Research Methods

Social constructionism-related theories provide informative approaches examining how social realities are created, negotiated, and upheld through human interactions. The study and intention to use CDA and influences of Foucauldian analysis offer robust, distinctive methods for comprehending how cultures form meaning, identity, and power relationships. Researchers may learn more about the underlying processes that shape our shared reality and advance a more critical and reflective knowledge of the world by utilising these approaches. This approach is vital when examining music curriculum, its origins and understanding the social nuances surrounding its existence, construction and rationale. In this portfolio, I intend to research the role of hegemony and valorisation of musical knowledge in government documents using CDA. The motivation behind this study is that it fulfils the requirements of being an unobtrusive study and allows for qualitative analysis using a social constructionist lens. To be successful in this project, a systematic approach will be necessary to understand the processes of CDA fully. My novice CDA researcher status justifies this at this stage, and using a rigorous research system will add rigour and academic integrity to this study. Mullets' (2018) seven CDA stages will be a powerful tool for this opening CDA research. Further justification will be explored in the methodology section of the portfolio.

Several factors must be considered to give this study validity in the vast world of research. Burr (2015) defines validity within the social constructionist realm as how well research methods align with the epistemological worldview. An immediate limitation of the unobtrusive research report that makes up this portfolio is that the shared understanding must come from the literature review as part of the CDA methodology. Despite being involved with research projects, I am a novice researcher with much to learn. Dunne, Pryor and Yates (2005), alongside Gergen (2015), claim that reflexive positionality is crucial in the validity of social constructionist research; this has been identified on several occasions in this essay and will remain at the forefront of ongoing research. Having dedicated the last few years of study to music curriculum within secondary education, further longitudinal research allows a deeper understanding of the shifts in musical knowledge paradigms (if any) over time (Wetherell, 2013). Within further research projects and my thesis, it will be necessary to include additional methods that align with the social constructionist epistemology; these may include the use of triangulation to strengthen validity (Denzin, 2017), further contextualisation detailing the way social phenomena are interpreted as highlighted by Geertz (1973) and further embedding myself into the longitudinal research design surrounding the music curriculum in secondary schools in the UK.

Synonymous with the criticisms of a social-constructionist worldview is the idea of bias and subjectivity without the researcher’s awareness. For this reason, it will be necessary to develop and continuously apply reflexive practices. It is essential to constantly examine the positionality and potential biases that may occur in future research. In doing this, a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of music curriculum discourse can be established, further enhancing the validity and integrity of the research (Hartman, 2016).

Reference List

Ashbee, R., 2021. Curriculum: Theory, Culture and the Subject Specialisms. Routledge.

Babbie, E. (2016). The Basics of Social Research (7th ed.). Cengage.

Bate, E. (2020) 'Justifying music in the national curriculum: The habit concept and the question of social justice and academic rigour,' British Journal of Music Education. Cambridge University Press, 37(1), pp. 3–15. doi: 10.1017/S0265051718000098.

Bates, V. C. (2017). Critical social class theory for music education. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 18(7). Retrieved from http://www.ijea.org/v18n7/.

Bryman, A. (2008). Social Research Methods. Oxford University Press.

Burr, V. (2015). Social constructionism. Routledge..

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge.

Charteris, J., & Smardon, D. (2019a). Student voice in learning: Instrumentalism and tokenism or opportunity for altering the status and positioning of students? Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 27(2), 305-323.

Charteris, J. and Smardon, D. (2019). The politics of student voice: Unravelling the multiple discourses articulated in schools. Cambridge Journal of Education, 49(1), pp.93-110.

Chouliaraki, L., & Fairclough, N. (1999). Discourse in Late Modernity: Rethinking Critical Discourse Analysis. Edinburgh University Press.

Clauhs, M., & Cremata, R. (2020). Student voice and choice in modern band curriculum development. Journal of Popular Music Education, 4(1), 101-116.

Comte, A. (1975). Auguste Comte and positivism: The essential writings. Transaction Publishers.

Dalladay, C. (2017). Growing Musicians in English secondary schools at Key Stage 3 (age 11–14). British Journal of Music Education, 34, 321-335.

Denzin, N. K. (2017). Critical Qualitative Inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(1), 8-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800416681864

DfE (Department for Education). Model Music Curriculum: Non-statutory guidance for the national curriculum in England. DfE. London: 2021.

Department For Education, 2022. The Power Of Music To Change Lives: A National Plan For Music Education. DfE.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Free Press.

Dunne, M., Pryor, J., & Yates, P. (2005). Becoming a Researcher: A Companion to the Research Process. McGraw-Hill Education.

Edwards, B., 2002. Deep insider research. Qualitative research journal, 2(1), pp.71-84

Elveton, R. O. (Ed.). (2020). The Phenomenology of Husserl: Selected Critical Readings (R. O. Elveton, Trans.). Taylor & Francis Group.

Fairclough, N. (1995). "Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language." Longman.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. Psychology Press.

Feichtinger, J., Fillafer, F. L., & Surman, J. (Eds.). (2018). The Worlds of Positivism: A Global Intellectual History, 1770–1930. Springer International Publishing.

Fink, A. (2003). How to manage, analyze, and interpret survey data (No. 9). Sage.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977 (C. Gordon, Ed.; C. Gordon, Trans.). Pantheon Books.

Fowler, R. (1997). Language in the News: Discourse and Ideology in the Press. Routledge.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Herder and Herder.

Gee, J. P. (2014). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures (Vol. 5019). Basic books.

Gergen, K. J. (1999). Agency: Social construction and relational action. Theory & Psychology, 9(1), 113-115.

Gergen, K. J. (2015). Culturally inclusive psychology from a constructionist standpoint. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 45(1), 95-107.

Giroux, H. A. (2020). On Critical Pedagogy. Bloomsbury Academic.

Griffin, S. M. (2011). Reflection on the social justice behind children's tales of in-and out-of-School Music Experiences. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 188, 77-92.

Hargreaves, D. J., Purves, R. M., Welch, G. F. & Marshall, N. A. (2007). Developing identities and attitudes in musicians and classroom music teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 665-682.

Hall, S. (1997). The Spectacle of the 'Other'. In S. Hall (Ed.), Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (pp. 225-290). Sage Publications.

Hartman, J. L. (2016). Insider Ethnography: A Reflexive Approach to Addressing Researcher Bias. Qualitative Sociology, 39(3), 305-323.

Hollis, M. (1994). The philosophy of social science: An introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Husserl, E. (1999). The essential Husserl: Basic writings in transcendental phenomenology. Indiana University Press.

Laclau, E. and Mouffe, C. (1985) Hegemony and Socialist Strategy. London: Verso

Mark, M. L. (1995). Music education history as prologue to the future: Practitioners and researchers. The Bulletin of Historical Research in Music Education, 16(2), 98-121.

Mark, M. L. (2014). Music education history and the future. Music Education, 3-12.

Mark, M. L. (2021). Music Education And The National Standards: A Historical Review. Visions of Research in Music Education, 16(6), 13.

Merton, R. K. (1972). Insiders and outsiders: A chapter in the sociology of knowledge. American journal of sociology, 78(1), 9-47.

Ministry of Housing, C. & L. G. (2019, September 26). English indices of deprivation 2019. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019

Mullet, D. R. (2018). A general critical discourse analysis framework for educational research. Journal of Advanced Academics, 29(2), 116-142.

Powney, J., & Watts, M. (2019). Inside the Inside: Revisiting Insider Research. Qualitative Research, 19(2), 245-263.

Priestley, M., 2021. Curriculum Development. [online] Professor Mark Priestley. Available at: <https://mrpriestley.wordpress.com/category/curriculum-development/>

Ricketts, CJ. (2022) Teacher Perceptions On Curriculum Design. University of Sussex. Unpublished presentation.

Shipman, M. D. (1997). The limitations of social research. Longman.

Shotter, J. (1993). Becoming someone: Identity and belonging (pp. 5-27). Newbury Park, CA, USA: Sage.

Spruce, G. (2015). Music education, social justice, and the “student voice”: Addressing student alienation through a dialogical conception of music education.

Spruce, G. (2016). Culture, society and musical learning. In Learning to teach music in the secondary school (pp. 17-31). Routledge.

Stavrou, N. E., & Papageorgi, I. (2021). ‘Turn up the volume and listen to my voice’: Students’ perceptions of Music in school. Research Studies in Music Education, 43(3), 366-385.

Steward, R. (2020). A Curriculum Guide for Middle Leaders: Intent, Implementation and Impact in Practice. Routledge.

Thomas, G. (2017). How to Do Your Research Project: A Guide for Students. SAGE Publications.

University of Sussex . (2018). Changes in secondary music curriculum provision over time 2016-18: Summary of the research by Dr Ally Daubney and Duncan Mackrill.

Van Dijk, T. A. (1993). "Principles of Critical Discourse Analysis." Discourse & Society, 4(2), 249-283.

Van Dijk, T. A. (2006). "Discourse and manipulation." Discourse & Society, 17(3), 359-383.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Weber, M. (1904). The Objectivity of Social Science and Social Policy. In The Methodology of the Social Sciences (E. A. Shils & H. A. Finch, Trans.). Free Press.

Wetherell, M. (2013). Affect and discourse–What’s the problem? From affect as excess to affective/discursive practice. Subjectivity, 6, 349-368.

Willig, C. (2014). Interpretation and analysis. The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis, 481.

Wodak, R. (2001). "What CDA is about: A summary of its history, important concepts and its developments." In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), "Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis" (pp. 1-14). Sage.

Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (2009). Critical discourse analysis: History, agenda, theory and methodology. Methods of critical discourse analysis, 2, 1-33.

Young, M.F.D. and Lambert, D. (2014). Knowledge and the future school : curriculum and social justice. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Comments